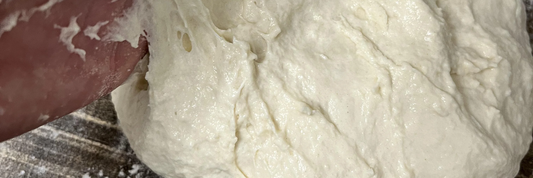

If you’ve ever wondered “Why is my dough sticky?” you’re not alone. Sticky dough is one of the most common frustrations for both beginner and experienced bakers. Whether you’re making bread, sourdough, pizza, or pastries, dough that clings to your hands and counter can make the process messy and confusing.

Understanding why your dough is sticky, from hydration levels to gluten development, humidity, and fermentation, can help you fix it quickly and prevent it in future bakes. In this guide, we’ll break down every possible cause, show you how to fix sticky dough step-by-step, and explain when a little stickiness is actually a good thing.

Understanding Dough Hydration & Stickiness

The Role of Hydration (Water : Flour Ratio)

“Hydration” refers to the ratio of water to flour in the dough, usually expressed as a percentage (water weight ÷ flour weight × 100%).

- When hydration is low (e.g. 55–65 %), dough tends to be firmer, easier to handle, and less sticky (often termed “stiff” or “firm” dough).

- As hydration rises (e.g. 70 % and above), the dough contains proportionally more water, is looser, and often feels sticky and slack—especially before sufficient gluten development.

- The flour’s absorption capacity is key: some flours can take more water before turning excessively sticky. Overestimating absorption leads to a dough that feels like a batter rather than a proper dough.

- Bakers often use “baker’s percentages” to precisely control hydration rather than vague volume measures.

Thus, if your dough feels too sticky, one of the first suspects is that your hydration is too high relative to the flour’s capacity or your handling method.

Why Is My Dough Sticky Even When I Measured Correctly? (Flour absorption, humidity)

Even if ingredient measurements seem correct on paper, several factors can push a dough into stickiness:

Flour variability / absorption differences:

- Two bags of “bread flour” may differ in protein, milling, and starch damage, altering absorption.

- Older or drier flour may absorb less water; fresher or slightly moist flour may absorb more, shifting your balance.

Ambient humidity & moisture in the air:

- In humid climates, flour may already contain extra moisture, reducing how much additional water it needs.

- Conversely, in very dry or low-humidity environments, dough may feel drier or require more water, tempting you to overshoot and overhydrate

Temperature effects:

- Warmer doughs amplify liquidity and can make the same hydration feel “wetter.”

- Cold dough may mask stickiness until it warms up.

Inclusion of other liquid ingredients: Ingredients like milk, eggs, yogurt, or liquid sweeteners also contribute water, so if recipes don’t fully account for them, total water content may be underestimated.

So even perfect measurement (on paper) doesn’t always translate to ideal handling—real‐world variables intervene.

Why Is My Dough Sticky During Autolyse / Early Mixing Stages

“Autolyse” refers to the rest period after mixing flour and water (and sometimes yeast, excluding salt) before later additions or full mixing.

-

Early on, the flour is still absorbing water and the gluten network is not yet developed. So the dough will naturally feel sticky and slack. Many bakers expect this phase to be “messy.”

-

During autolyse, water gets drawn into the flour particles and starches swell; glutenin and gliadin begin bonding. Until that bonding is advanced, the dough lacks strength and cohesion.

-

If your hydration is high, the early stage may be especially loose and sticky—this is “normal” to an extent in high hydration doughs.

-

Allowing the autolyse to fully play out (say 20–60 minutes) before aggressive mixing helps the flour fully absorb water and start forming structure, which can reduce stickiness later.

If you rush through autolyse or skip it, you may prolong or worsen the sticky phase downstream.

Why Is My Dough Sticky After Kneading / During Bulk Fermentation

By this stage the dough has undergone kneading or folding, and is fermenting in bulk. Sticky behavior here can indicate several issues:

Underdeveloped gluten network

- If kneading or folding was insufficient, the gluten network remains weak and cannot hold water or gases effectively, so the dough remains sloppy.

- The dough may feel sticky, lack elasticity, and tear easily rather than stretching.

Overfermentation / weakening network

- Extended fermentation (especially warm) can degrade gluten (enzymes break bonds), making the dough slack and sticky again.

- Gas pressure can stretch the network too far; when the dough nears its expansion limit, the integrity is compromised and stickiness returns.

Temperature influence

- Warm bulk fermentation accelerates biochemical activity (enzyme action, gas expansion), increasing liquidity and making the dough “looser.”

- The interior of the mass may become more fluid as gases build.

High hydration limit: At hydration beyond ~65–68 %, even well-developed dough may always feel somewhat sticky and difficult to grip, despite good structure.

Thus stickiness after kneading or in bulk ferment is a sign to check gluten strength, fermentation length, and hydration balance.

Why Is My Dough Sticky at High Hydration vs Low Hydration Doughs

The contrast between high and low hydration doughs helps clarify when stickiness is expected vs problematic:

Low hydration doughs (say ≤ 60 %)

- Tend to be drier, stiffer, less extensible, and easier to manage.

- Stickiness is minimal except maybe slight tack on hands or surface.

- They are more forgiving for novices but yield tighter crumb and less open structure.

High hydration doughs (≥ 70 % and above)

- Yield a moister, more open crumb and lighter texture, prized for artisan breads.

- But they are more difficult to handle: more sticky, fluid, and require gentle techniques (folding rather than classic kneading).

- Even when the gluten is well developed, a very wet dough may retain a “slack” or tacky feel.

- Bakers often expect that high hydration doughs will feel sticky initially, but over time (folds + rest) they become more manageable.

In summary, low hydration doughs resist stickiness but offer less open texture; high hydration doughs bring stickiness challenges but enable superior crumb, if managed well.

Causes of Sticky Dough — Diagnosing the Problem

Here are the common root causes of sticky dough, with explanation of how each contributes and how to identify it.

Too Much Liquid / Water in the Recipe

-

The simplest cause: you added more water (or liquid) than the flour (and other ingredients) can absorb.

-

This can occur from mis-reading a recipe, using more wet ingredients than accounted for, or increasing hydration “just because.”

-

The dough may behave more like a batter, spreading across surfaces rather than resisting shape.

-

Fix: reduce water, add flour gradually in small increments, or choose a flour with higher absorption.

-

Many bakers advise starting with 60 % of the liquid and adding more gradually to avoid overshooting.

Flour Type (Protein / Strength / Absorption)

-

Flours with higher protein (e.g. “bread flour”) form more gluten and tend to absorb more water, giving the dough more structure.

-

Lower-protein flours or pastry / all-purpose flours have less gluten potential, so at a given hydration they may feel looser and more sticky.

-

Whole grain flours, bran, and fibers interrupt gluten formation and reduce absorption uniformity, making dough stickier.

-

Some flours are milled more finely or have more damaged starch, which changes how they absorb water.

-

If you swapped flour types (e.g. to a softer flour) without adjusting hydration, the result may be a sticky dough.

Inaccurate Measurement (volume vs weight)

-

Measuring by volume (cups) can lead to large variation: a “cup” of flour can vary in density, compaction, humidity etc.

-

Weighing ingredients (grams) with a scale is far more precise and reduces the risk of too much water relative to flour.

-

Many sticky-dough issues stem from volume measurements that overestimate the flour portion.

Insufficient Gluten Development / Inadequate Kneading or Folding

-

Gluten (from glutenin + gliadin proteins) gives dough its elastic network, which can trap water and gas; underdevelopment means the water remains “free” and makes the dough sticky.

-

If dough isn’t kneaded or folded enough (mechanically or via rest cycles), the network doesn’t fully form.

-

A weak network cannot resist flow, so the dough clings to surfaces or your hands.

-

Techniques (stretch & fold, coil fold, interval kneading) help develop gluten gradually, especially for wetter doughs.

Lack of Salt (or improper salt timing)

-

Salt strengthens the gluten network by tightening bonds and controlling enzyme activity. Too little salt weakens the network, causing a slack, sticky dough.

-

If salt is added too early (on strong flour) or too late, it can skew gluten development. Some bakers use delayed salt methods.

-

Proper salt percentage (often ~2–3 % of flour weight) helps improve dough consistency and reduce stickiness.

Enriched Ingredients (Sugar, Fats, Eggs, Milk)

-

Fats (butter, oil) coat gluten proteins, interfering with bond formation; this leads to weaker structure and stickier dough.

-

Sugars compete for water, delaying hydration of proteins and starches; initially the dough may feel sticky until gluten “catches up.”

-

Dairy, eggs, or other liquid enrichments add extra water and complexity; they also alter gluten formation dynamics.

-

Enriched doughs (e.g. brioche) are known to be stickier and trickier to manage if overhydrated.

Warm Temperature / High Ambient Humidity

-

Heat speeds enzymatic and microbial activity, making dough more fluid and increasingly sticky.

-

High humidity adds ambient moisture to flour or surfaces, making the dough behave wetter.

-

Warm rooms accelerate fermentation and gas expansion, further pushing stickiness.

Over-fermentation / Overproofing / Weakening Gluten

-

In long or warm fermentations, protease enzymes and gas expansion can degrade or overstretch the gluten network, making it weaker and sloppier.

-

The dough may lose structure, become slack, and again return to sticky behavior.

-

Especially with high hydration doughs, overproofing quickly turns manageable dough into a sticky mess.

Starter Issues (for sourdough): immature starter, runny starter

-

If your sourdough starter is too liquid or weak (low strength), it may introduce excess fluid or not contribute structure, making the dough overly slack.

-

A stale or underfed starter may produce acids or weaken gluten integrity, further contributing to stickiness.

-

In sourdough formulas, proportion adjustments (starter hydration, water content) must be precise; misbalance can tip the dough into the sticky realm.

Dough Handling / Mixing Technique Errors

-

Over-mixing (especially in enriched or delicate doughs) can break gluten or overheat the dough, weakening structure.

-

Rough handling, tearing, or constant reworking can damage networks and make dough clingy.

-

Not using folding or rest periods means the dough never relaxes or reorganizes; it stays tense and sticky.

-

Failing to use bench scrapers or letting dough adhere to surfaces can exacerbate stickiness during manipulation.

Too Little Resting / Autolyse Time

-

Rest periods allow water to fully absorb into flour and for gluten bonds to begin forming in a relaxed state. Without rest, the dough stays rough and sticky.

-

Skipping or shortening autolyse or bench rests means you force structure prematurely, which can produce weaker, stickier dough.

-

Allowing intervals of rest (e.g. after stretching, folding) helps the dough reorganize and reduce surface stickiness over time.

How to Fix Sticky Dough — Step-by-Step Remedies

Below are methods to rescue or better manage a sticky dough. Use them carefully and incrementally, so you don’t overcorrect and end up with a dry, tough dough.

Adjust the Hydration: How Much Water to Remove or Hold Back

-

If your dough is very sticky and clearly over-hydrated, consider reducing the water slightly in your next iteration (e.g. subtract 2–5 % of water by weight).

-

For example, if your recipe calls for 300 g water with 500 g flour (60 % hydration), try 285 g or 290 g water instead.

-

-

During mixing, you can also hold back a portion of the water (say 5–10 %) and add it gradually as the dough comes together; only add more if needed.

-

Be cautious: removing or withholding too much water can make the dough too stiff and limit gluten development.

-

Many bakers find that halving or moderating water adjustments is safer than large swings.

Add Flour Gradually (teaspoon by teaspoon) — Tactics and Warnings

-

If the dough is sticky beyond control, you can incorporate extra flour, but do so very gradually—a teaspoon or two at a time (≈ 5–10 g) into the dough.

-

Work the extra flour in slowly: mix lightly, let it absorb, then judge further.

-

Warnings / caveats:

-

Overdoing flour addition dries out dough, densifies crumb, reduces oven spring.

-

It disturbs your hydration ratio, potentially making the dough inconsistent.

-

Some of the flour you add might never fully hydrate, leaving dry pockets.

-

-

Many experienced bakers advise: avoid “dusting everything with flour” indiscriminately.

Use Stretch & Fold or Coil Folds for Gluten Development

-

Rather than aggressive kneading, stretch & fold (or coil folding) is gentler and effective for developing strength in wetter doughs.

-

During bulk fermentation, you gently stretch one side of the dough upward and fold it over the center; rotate and repeat on all sides.

-

This helps reorganize gluten, strengthen structure, and reduce slackiness.

-

-

These intermittent folds help the dough gradually handle its water content better, making it less sticky over time.

-

Many artisan bakers favor stretch-and-fold over classic kneading for high hydration doughs.

Proper Kneading Timing & Methods

-

If using a classic kneading method, ensure you knead long enough (but not excessively) to develop a cohesive gluten network.

-

Sometimes, the dough is sticky early in kneading but will “clean up” after several more minutes, as the gluten network forms and binds water.

-

Use quick, confident movements (rather than fiddling) to minimize sticking.

-

Consider mixing until just combined, letting it rest (autolyse) or resting mid-knead, then finishing the knead.

-

If kneading by hand is too messy, a stand mixer with dough hook (on low speed) may help, but monitor closely to avoid overheating or overworking.

Incorporate Salt at the Right Moment

-

Salt strengthens gluten by tightening protein bonds and controlling enzyme action. If your dough is weak, it may stay sticky.

-

Using ~2–3 % of flour weight as salt is common.

-

Some bakers use delayed salt (mix flour + water first, then add salt later) to allow initial gluten formation. This can help with very “strong flour” doughs.

-

If you added salt too early or too late, the gluten network might not have developed optimally; adjusting timing in future batches may help.

Use Oil, Flour, or Water on Work Surface or Hands

-

Oil: lightly oil your hands and work surface to minimize sticking. This is gentler than flour dusting and doesn’t alter hydration much.

-

Flour: dust just a little flour on the surface or hands (not too much). Use sparingly to avoid drying the dough.

-

Water: in some cases, wetting your hands (slightly damp) helps manipulate dough rather than sticking; for very wet doughs, some bakers prefer wet hands to dry hands.

-

Use a bench scraper / dough scraper to lift, fold, clean edges, and help coax the dough rather than forcing it. This tool is one of the most recommended for sticky dough work.

Chill the Dough / Refrigerate to Reduce Stickiness

-

Cooling the dough helps slow enzyme activity, firm up fats, diminish liquidity, and make it easier to handle.

-

Place the dough (lightly oiled to prevent drying) in the fridge during bulk fermentation or before shaping; after a few hours it may feel less tacky.

-

Cold fermentation (e.g. overnight) also lets flavor develop while improving structure and manageability.

-

Use a loosely covered, oiled bowl or container so the dough doesn’t stick or dry on the outer surface.

Resting / Bench Rest / Autolyse Periods to Ease Stickiness

-

Rests are crucial: letting dough sit (bench rest or autolyse) allows water to absorb fully and gluten to start bonding.

-

During autolyse, avoid mixing salt and yeast (or delay their addition), so flour + water can gently hydrate and begin structure formation.

-

After aggressive mixing or folding, allow short rests (10–20 minutes) so the dough relaxes, moisture redistributes, and stickiness lessens.

-

Especially in early stages (first 10–20 minutes), resist the urge to force handling; let dough settle.

Extend Bulk Fermentation Slowly (Cold Fermentation)

-

Doing bulk fermentation in cooler temperature (e.g. in the fridge or a cooler room) slows fermentation and gives the dough time to mature structurally without excessive enzymatic breakdown, which can re-introduce slackness.

-

A slower rise maintains strength and avoids the dough becoming too slack and sticky mid-process.

-

This method also allows more flexibility in timing (you can shape later when dough is more manageable).

Adjust Ingredients (Use Stronger Flour, Reduce Enriching Add-Ons)

-

If sticky dough is recurring, consider switching to a higher protein / stronger flour (bread or “strong” flour) that supports greater absorption and structure.

-

If your recipe is enriched (with sugar, fat, eggs, milk), reduce or moderate these additions, or adjust water accordingly (since these ingredients contribute moisture and interfere with gluten).

-

In whole grain or bran doughs, consider blending with white bread flour to improve structure and reduce stickiness.

-

Use fresher, well-stored flour that hasn’t absorbed ambient moisture (i.e. store flour in cool, dry, airtight containers).

Use Tools: Bench Scraper, Dough Scraper, Folding Techniques

-

A bench scraper / dough scraper is indispensable: use it to lift, coax, fold, and clean stuck dough rather than trying to peel it by hand.

-

Use the scraper to reincorporate bits of dough stuck on the surface back into the main mass.

-

During stretch & fold cycles, use the scraper to help turn edges and manage slack dough without tearing.

-

You can also use curved metal “scotch” scrapers, bowl scrapers, or plastic spatulas to minimize sticky contact.

When to Accept Slight Stickiness — Knowing When It’s “Okay”

-

Some stickiness is normal, especially in high hydration or artisan doughs. Doughs of 70 %+ hydration often remain tacky even when fully developed.

-

Aim for a dough that is tacky but not drenched in wetness — it should come off your fingers with a slight tug, not smear or liquefy.

-

If stickiness doesn’t prevent shaping, rising, and baking well, it may be tolerable.

-

Overcorrecting to eliminate all tack often leads to stiff, dry dough with poor oven spring.

-

With experience, you’ll develop a “touch feel” for when to stop intervening and let the dough do its work.

Specific Cases: Sticky Dough in Different Applications

Why Is My Bread Dough Sticky? (Lean and Enriched Loaves)

Lean loaves (simple flour + water + yeast + salt)

-

Even lean doughs can feel sticky early on, especially with moderate to high hydration. The gluten network hasn't fully formed yet, so water is freer and tends to cling.

-

If stickiness persists into shaping, it often signals under-kneading or that hydration is too high for the flour’s absorption.

-

Overfermentation (especially in warm conditions) can cause a lean dough to become slack and sticky again.

Enriched loaves (with sugar, butter, milk, eggs)

-

The fats coat gluten proteins and inhibit bond formation, weakening the network, which encourages stickiness.

-

Milk, eggs, and sugar add extra “free water” to the system, increasing liquidity.

-

Because of these ingredients, enriched doughs are more sensitive: small miscalculations in water or technique lead to noticeable stickiness.

-

Enriched loaves are often managed with techniques like tangzhong (a cooked flour-water paste) to stabilize moisture while reducing stickiness in handling (this method “locks in” moisture) (mentioned by Bon Appétit in relation to soft breads)

What to watch / diagnose

-

If sticky but still rising, the problem is likely structural (gluten strength) rather than hydration alone.

-

If the dough never develops elasticity or tears easily, it suggests under-development or interference (from fats/sugar).

-

Enriched sticky dough may require lower hydration or more rest/folds to let the gluten “catch up.”

Why Is My Sourdough Dough Sticky?

Sourdough presents its own challenges:

-

Many sourdough recipes use relatively high hydration, making them more liable to feel sticky.

-

Overfermentation is especially problematic: if the bulk fermentation goes too long (or the dough doubles or triples), the dough becomes slack, sticky, weak, and may smell alcoholic.

-

A weak or immature starter (or one with low activity) can fail to develop sufficient structure, leaving the dough loose and sticky.

Why Is My Pizza Dough Sticky?

Pizza dough often hovers between manageable hydration and sticky risk:

-

The most common reason is too high hydration — too much water relative to flour.

-

Because pizza dough is expected to be stretchy, some tackiness is acceptable, but excess stickiness impairs handling (shaping, stretching) and can cause it to stick to your surfaces.

-

Sometimes flour isn’t fully incorporated (clumping), leaving wet pockets.

-

Under-kneading is another culprit: if gluten isn’t developed, the dough won’t resist flow and will stick.

-

Overproofing or slack dough (especially in long, slow proofs) can reduce strength and bring back stickiness.

Diagnostic signals

-

If it’s sticky immediately after mixing, hydration or mixing technique is suspect.

-

If it’s okay early but becomes sticky during shaping, overfermentation or weakening gluten is likely.

-

Some stickiness is acceptable — pizza dough doesn’t need to be stiff; it must remain workable.

Tips

-

Use the “double hydration” trick: hold back some water initially, knead until a moderate consistency, then gradually add the remainder.

-

Let the dough rest briefly mid-mix to let flour absorb.

-

Use dusting or oiling of working surface to reduce adhesion.

-

Because sourdough fermentation involves acid production and enzymatic action, extended fermentation may degrade gluten over time, reducing its ability to bind water.

-

Some sourdough bakers deliberately expect and accept a degree of stickiness early on, then manage it via folds, cold ferment, stretching, etc.

Clues / diagnostics

-

If your dough becomes a “wet puddle” or lacks any strength when you try to turn or shape, it likely over-fermented.

-

If it’s sticky early but firms up after several stretch/fold cycles, it’s likely just underdeveloped at first, not a fatal flaw.

Why Is My Cookie / Pastry / Cake Dough Sticky? (Temperature, fats)

These are different from yeast doughs — many are not intended to develop gluten extensively:

-

Temperature sensitivity: These doughs often contain butter or fat that softens with heat. Warm room or warm hands will soften fats, making dough stickier.

-

High fat/sugar content: These ingredients don’t form structural networks; instead they interfere with moisture absorption and weaken cohesion, so sticky dough is common.

-

Lower structural gluten: Because you don’t want strong gluten in pastries, they are often “weak” by design and more prone to stickiness.

-

Liquid additions: Milk, eggs, and other liquids in batters or pastry dough can tip the balance toward stickiness.

-

Overmixing: In cookie or cake dough, overmixing can break down structure, releasing more moisture and making it sticky.

What to check

-

If dough becomes very sticky on warm days or in warm kitchens, temperature is a key factor.

-

If a pastry dough is stickier than normal, chill it (dough temperature matters more here).

-

If sugar proportion is high or there’s added liquids, tweak proportions or chilling steps.

Why Is My Enriched Dough (e.g., Brioche, Challah) Sticky?

Enriched doughs are notoriously challenging:

-

They contain high proportions of fat (butter, oil), sugar, eggs, milk — all of which add free moisture or inhibit gluten networking.

-

The fats coat proteins, reduce friction between gluten strands, and weaken bond formation, increasing stickiness.

-

The added liquids (milk, eggs) increase the total “free water” content.

-

Because of their rich composition, small adjustments in hydration or technique have outsized impact on handling properties.

-

Using a tangzhong or water roux (pre-cooked flour-water paste) is a known method to allow richer doughs to take more water without becoming unmanageably sticky (see Bon Appétit reference).

Indicators

-

The dough may feel sticky until it cools or rests; chilling often helps significantly.

-

If the dough never develops elasticity or always resists shaping, the enrichments may be too aggressive relative to your flour or process.

Why Is My Whole-Grain / Rye Dough Sticky?

Whole-grain and rye flours bring unique challenges:

-

The bran and fiber in whole-grain flours cut through gluten strands, weakening network continuity and reducing cohesion.

-

Rye contains less gluten-forming protein, so even at lower hydration, dough can feel sticky because the structure is weak.

-

Whole-grain flours often require more water to hydrate fibrous materials; this extra hydration can push dough toward stickiness.

-

The water absorbed by bran and fiber sometimes competes with protein hydration, leaving “free water” in the dough.

-

Rye’s starches are more gelatinous and hold water differently, often making dough more tacky.

Clues

-

If sticky despite moderate hydration, structural weakness is likely.

-

If the dough does not “clean up” with kneading/folding, it might simply lack the capacity to become non-sticky.

-

In mixed flours (e.g. part rye, part wheat), you may need to reduce total hydration or reinforce with stronger flour.

Conclusion

A sticky dough doesn’t always mean something has gone wrong. In fact, slight tackiness often signals proper hydration and good gluten development, especially for artisan breads or sourdoughs.

The key is learning to tell the difference between too sticky and just right. By understanding hydration ratios, flour strength, fermentation timing, and handling techniques, you can control your dough’s texture and bake with confidence.

The next time you ask yourself “Why is my dough sticky?” remember: with the right balance of science and feel, every sticky start can lead to a beautifully soft, airy loaf.